Hear, hear! A post about Richard Armitage! I come back on topic after many months. I could not miss to write something about “Romeo & Juliet – A novel”, the last Audible production performed by Mr. Armitage, written by David Hewson. Needless to say that what comes next is full of spoilers and should you prefer not to know anything about this before hearing the audiobook, you’re kindly invited to read this afterwards.

THE PERFORMANCE

Richard Armitage is brilliant. His ability to work in this medium improves with each reading. If someone should ask me “show me how good is this Armitage you admire so much” I would reply “just hear him performing the part of a stammering fifteen-year-old girl in “The Convenient Marriage”. Richard Armitage does not “imitate” voices, the result would be perhaps ridiculous, but he manages to speak with tones of voice that are like brush-strokes of the characters’ psyche, triggering our imagination. I will confess something: although I love radio dramas, I’m not very fond of audio-books. If they’re not performed by Richard Armitage they usually bore me to death, and I assure you that I’ve tried quite a few. For instance, the second hearing of “Macbeth – A novel” lingers in my Audible application and, frankly speaking, the first one required a huge effort of concentration. I have also a multi-read version of Bram Stoker’s Dracula waiting to be finished for more than a year. The only audiobook not narrated by him that I have heard several times is “A new kind of war” performed by Dominic Mafham, whose technique is similar to Richard Armitage’s; but there are no female characters in that novel, the comparison of the performances of both actors cannot be complete.

I have a favourite voice in each of Richard Armitage’s audiobooks: Damerel in “Venetia”, the aunt Betsey Trotwood in “David Copperfield” (by the way I would like very much to know if he had Lesley Manville’s performance in “Mr. Turner” in mind when rehearsing that voice) or Claudius in “Hamlet”. In Romeo & Juliet my favourite one is undoubtedly Mercutio. It reminds me his Mr. Lovelace in BBC’s Radio Drama Clarissa.

Mercutio is a brawler, an ambiguous character, with a dark, self-destructive nature. His “Queen Mab” speech has been beautifully adapted; when he walks out the Capulet’s party, drunk, with Benvolio and Romeo, his drunkard speech about the “beautiful” Anna and the tumble/fumble game of words is impregnated with tenderness and melancholy. “Death will be the death of all of us”, Mercutio said that afternoon. He’s the brimstone that will kindle the tragedy, the angel of death. His curse, “a plague on both your bloody houses”, when he lies dying sounds like a lame excuse.

THE STORY

The novel, as the previous Macbeth and Hamlet written together with A.J.Hartley, is an attempt to “fill in the gaps” of the many unanswered questions that may arise in a three-hour play, for instance, how could Romeo and Juliet fall in love with only a few verses. The narrative rhythm is compelling and gripping. It’s very difficult during the first hearing to decide where to stop or make a pause, as I wanted to know “what will happen next”. I have appreciated the little stories behind each character, as for instance those of Friar Lawrence and his brother Nico, and the description of a real historical character I’ve read of many times, Isabella d’Este. She’s a mix between Alice’s Queen of Hearts and Ben Wishaw’s Richard II in “The Hollow Crown” (monkey included). The voice used by Richard Armitage for Isabella, with a strong Italian accent, completes the picture of how a Renaissance ruler locked in a gilded cage away from the reality lived by their subjects should be like. It is perhaps an extreme caricature of what the real Isabella d’Este was, but, as I have never feel sympathy for her (I’m rather on the side of her wicked sister-in-law) I cannot but enjoy this version.

I expected some changes in the known plot of Shakespeare’s play, therefore I was not shocked when I heard that at the end, Juliet survive. Honestly, I was definitely more outraged by the miraculous survival of Messala and the chessy happy-ending in the recent movie-version of Ben-Hur. Furthermore, Juliet’s decision of starting a new life alone and away from Verona is in harmony with this Juliet.

The main issue with this novel is that, unlike “Hamlet”, it endures very poorly further hearings. In this case, once the curiosity to know “what happens next” is over, issues arise. And an issue with a name and surname: Juliet Capulet.

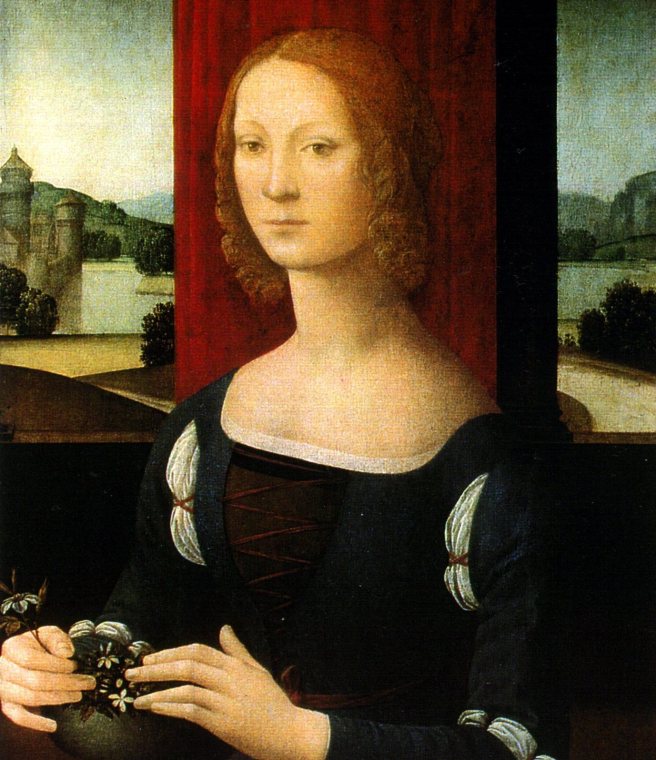

Historical novels are very difficult to write, and the alchemy to make a successful one as dark and unfathomable as the philosopher’s stone. Needless to say that “successful” does not equal to me automatically to best seller (I’m the one who abandoned “World Without End” in page 800); this is a post in a personal blog and I’m writing about what I like. I’m rather intolerant, when reading historical or period novels, with characters that are not coherent with the time and place where the novel is set. And this particular Juliet is any century in the future but late XVth. One of the most relevant woman in Italy those years was Caterina Sforza Riario. She was engaged when she was still a child, consummated her marriage as soon as nature allowed it, and by twenty she was already the mother of four children. The duty of a noble woman in that period was to get married and give birth as many heirs as possible; they were bred for that and Caterina did, although she was an intelligent, independent woman. When her husband, Girolamo Riario, died, she ruled her lands with such a competence and belligerence that she was known as “the tigress of Forlì”. She has a place in one of history’s most famous quotations. When Forlì was sieged by an army and they threatened to kill one of her sons, kept as an hostage, if she didn’t surrender the castle, her answer was to climb up the battlements, lift up her skirts, show her sex to the besiegers and shout: “kill him if you want, I have the mold here to make many more”. If I cannot imagine a woman like Caterina saying his father the Duke of Milan, that she would prefer not to marry Girolamo Riario, to me is somewhat difficult to accept a Juliet of Verona saying his father that she would not marry Paris. When she discusses with Friar Lawrence the equality of the marriage vows (I’d prefer not to comment Romeo’s reaction after her exploit), or wonders, after making love with Romeo for the first time, if the deed was not rather too quick, it takes almost an act of faith to accept this without even rising a brow.

There’s another peculiarity of this novel that is worth discussing: the abundance of words in Italian. This shouldn’t be an issue to me, speaking this language daily (although it is, for a reason that I will explain later on), but I’m afraid that this massive presence of Italian words prevent many readers to understand the text. When I listened to “Hamlet”, I only learned after reading the written version, that what I thought was “the horizon” was in fact “the Øresund”, the Northern Sea. I wonder what the average hearer will understand of the sentence “the piano nobile in the palazzo”. Perhaps those with a more vivid imagination think that one of the entertainments in Capulet’s party was to gather around a luxurious Renaissance musical instrument (never mind if pianos did not exist yet). In my opinion the words in Italian are definitely too many for an audio book (and in the case of the “piano nobile”, not even necessary). In a printed one, foreign names or words in italics may lead the readers, if they feel like, to look what that specific word mean or where a certain place is. Nevertheless in an audio format it may be misleading, when not directly irritating. Some of the Italian words are pronounced with a misplaced accent. I’m not blaming Richard Armitage for it: as someone told him how to pronounce his German lines in Berlin Station (and apparently he was told right), someone had to tell him not only how “gn” sounded like in Italian, but that the accent in “Signoria”, is in the second “i” and not in the “o”. And many other words: antica and not antica, Brancacci and not Brancacci, or Esposito and not Esposito. This last misplaced accent was the one that made me literally jump in the couch, as this recalls to Italian speakers the dubbing of old Laurel and Hardy movies. Definitely not what David Hewson wanted to recall in anyone hearing his work.

To make Isabella d’Este sister-in-law of Lucrezia Borgia three years before their time is an artistic license, I understand the reason why the autor “anticipated” the event for narrative purposes (although I’d have appreciated a mention about this license in the afterword of the book or his posts about the novel). This “accents issue” is a big editing mistake that would have been extremely easy to avoid, and I cannot understand why in a production like this (we’re talking of Audible, not of three friends recording a fan-fiction with their phone) the foreign words have been dealt with such superficiality. At least here, unlike in “Hamlet”, Medici was the pronounced with the right accent, not with a Laurel-Hardy Medici.